As a 30-year-old academic, my world has always been digital. I’ve never had to rely on physical card catalogs or spend weeks waiting for an inter-library loan. Yet, until a few years ago, the core of my mathematical work felt surprisingly traditional. The creative process was a solitary loop between my brain, a screen, and a blackboard. The tools were passive; they did exactly what I told them to.

Then, a new kind of apprentice showed up in my workshop. It was tireless, absurdly fast, and had read more papers than I could ever hope to. It was also, I would soon discover, prone to fits of invention and in need of constant supervision. This apprentice, of course, was AI.

A Mathematician Wears Four Hats

To understand the AI’s role, you first have to understand what a mathematician actually does. It’s not just solving equations. Our work is a fluid, creative process, and my time is split between four intertwined roles.

1. The Architect: This is the soul of the work, but it’s not as solitary as it sounds. A real-world architect doesn’t just stare at an empty landscape; they draw inspiration from existing buildings, site constraints, and conversations with clients. For the mathematician, it’s exactly the same. The “blueprint” for new math rarely emerges from a vacuum. Instead, it’s often a creative synthesis — a spark from a discussion with a colleague, a lecture on a seemingly unrelated topic, or an idea from a new field. Crucially, just as an architect is motivated by clients, a core motivation for mathematics also comes from challenges posed by other sciences like physics, biology, or computer science. This is where we ask the big “what if” questions: What if we could turn this intuition from physics into a rigorous mathematical tool? What if we could unite these two seemingly different fields under one theory? What if this familiar object has a completely different interpretation we’ve never considered? It’s about having the vision to see a potential new building where others just see a collection of materials. It requires intuition, taste, and the creative leap of charting a path through abstraction.

2. The Engineer: The Engineer takes the Architect’s dreamy blueprints and figures out how to actually build them. Often, the Architect’s vision is impossibly grand, and the Engineer’s first job is to provide a reality check, saying, “That magnificent crystal tower you designed is impossible to build right now. But we could build a smaller, stronger stone version first to test the principles.” In mathematics, this means tackling a simplified version of the main problem. These “simple” problems are often incredibly challenging themselves, and solving them is essential to understanding the real structure of the main goal. This creates a constant dialogue between what is desirable (the Architect) and what is possible (the Engineer).

3. The Historian: Before you can build, you must study the masters. But this isn’t just about knowing what’s been done; a historian doesn’t just memorize dates, they seek to understand the flow of events. For a mathematician, this means the primary goal isn’t merely to be aware of existing theorems, but to learn the techniques and powerful methods developed by our predecessors. It’s a slow, meticulous process of standing on the shoulders of giants to see not just what they saw, but how they saw it.

4. The Orator & Lawyer: This final phase has two faces. The Lawyer is the role most people picture: building an absolutely airtight case. Every single logical step of the final proof must be written down with uncompromising precision, able to withstand the intense scrutiny of other experts who are trained to find any loophole. But that’s not enough. A correct but incomprehensible proof is a failure. That’s where the Orator comes in. The Orator’s job is to present the argument with creativity and clarity, telling a story that allows another human to not just verify the result, but to understand it, appreciate it, and build upon it. This act of clear, elegant communication is a deeply creative and vital part of the work.

The Good Apprentice: Where AI Shines

So, where does my AI apprentice fit into this workshop? Its performance has been a mix of astonishing success and frustrating failure, starting with the successes. As an assistant to the Engineer, AI performs like a brilliant intern. It can take on tasks that are straightforward but laborious. For instance, it can write code for a simulation in minutes — a task that might have taken me half a day — or perform a routine, but tedious and time-consuming computation. It’s not always perfect — like a student, it sometimes makes mistakes in these calculations and its work needs to be double-checked. But its speed is revolutionary. What researcher wouldn’t trade hours of tedious work for more time to think creatively?

But its most profound impact has been on the role of the Historian, despite some disastrous first encounters. I started with the tools everyone was talking about: ChatGPT and the standard version of Gemini Pro. My experience with Gemini Pro was particularly memorable. It was the equivalent of laying out your reasoning to a history enthusiast like this: “Look, I know for a fact Napoleon died in exile. Working backward from that, there must have been a single, decisive battle that ended his career for good. I’m trying to find the name of that battle.” You’re not asking because you forgot; you’re asking because your logic dictates that this fact must exist. Then, the AI, with unnerving confidence, tells you to consult a well-known book on Decisive European Conflicts and points you to a specific page. You check the source, only to find that the page describes the Battle of Hastings in 1066. To make matters worse, the book doesn’t contain the Battle of Waterloo at all. The AI hadn’t just misunderstood my reasoning; it had confidently invented a reference that was both plausible and useless. It’s a chilling thought, isn’t it? An assistant that lies with perfect confidence?

I was ready to write it off. But then I tried again, this time using Gemini Pro with its deep research capabilities explicitly. The difference was night and day. I gave it the same non-trivial question. Instead of hallucinating, it dug deep into actual academic sources. Within minutes, it identified a paper, published in The Indian Journal of Statistics in 1979, that contained the exact result I was looking for. A result that could have taken me weeks of library work to find, it delivered in moments. I had gone from a confident but clueless assistant to a true, world-class research librarian. It excels at finding the “what” — the specific result, the forgotten paper. The human historian’s job is then to digest that result and understand the “how” — the deep techniques within it.

The Flawed Apprentice: Where AI Fails

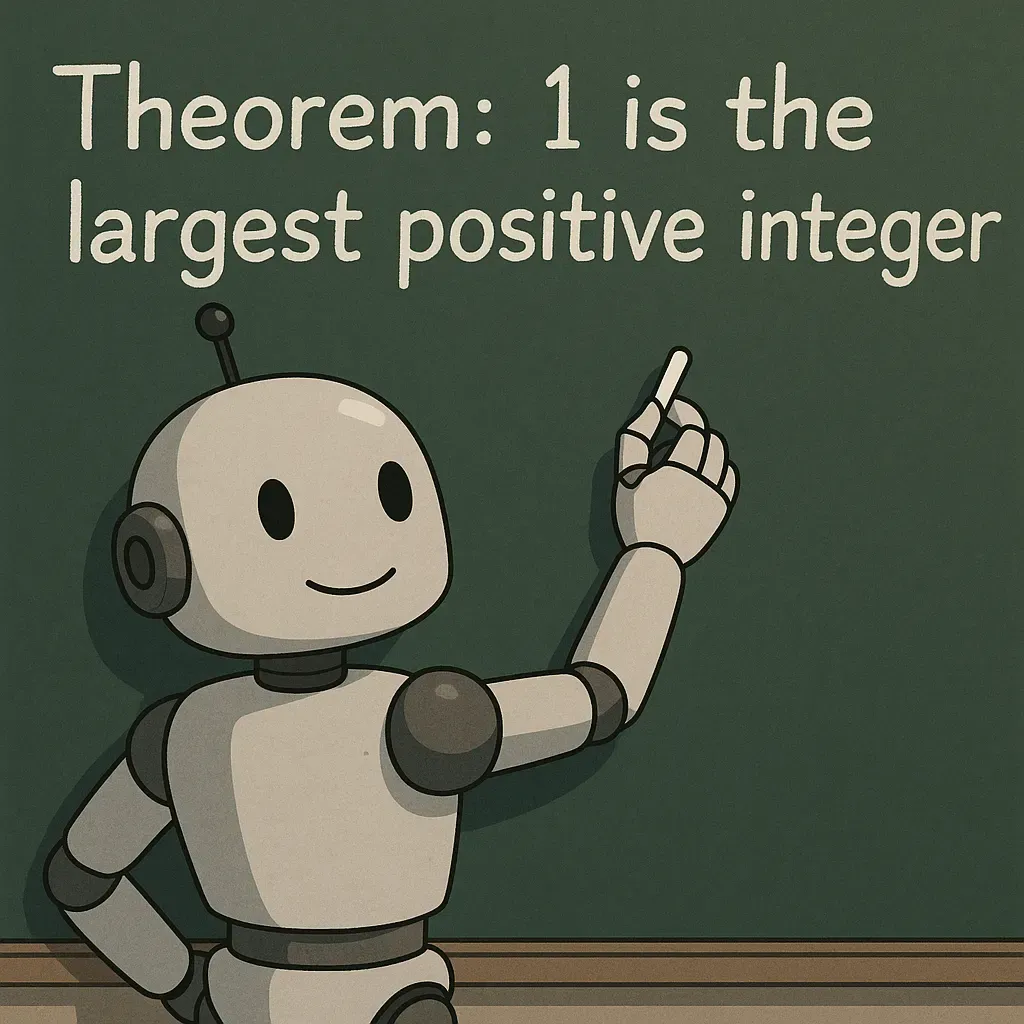

This experience highlights AI’s limits. While the right tool can be a phenomenal Historian, its most dangerous failure is as a Lawyer. Its ability to construct a sound argument is fundamentally broken. I have had multiple experiences where the AI has “proven” a statement for me, but its argument is riddled with gaping logical holes. Would you want your life or liberty defended by such a lawyer? When I point out a flaw, it often fails to recognize the fundamental issue. Instead, it might apologize and offer a “fix” that is just as flawed, or even double down on its original mistake. This is where its weaknesses combine in a particularly dangerous way. Its confident-but-fake Historian persona feeds its incompetence as a Lawyer. It will invent a theorem out of thin air, give it a plausible-sounding name, and then use this non-existent result as a key piece of evidence in its faulty proof. It builds self-contradicting arguments while hiding behind the authority of sources that don’t exist. An apprentice like this can’t just be supervised; it has to be fundamentally distrusted when it comes to building a valid argument.

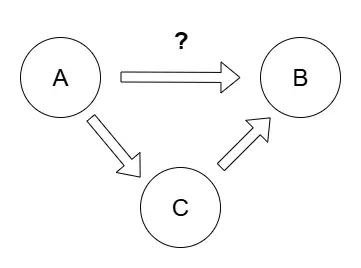

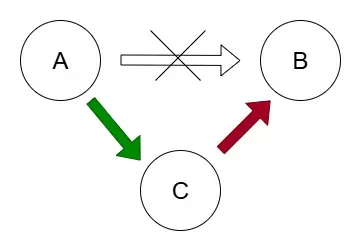

Let me give you a specific example. I once asked a seemingly simple question about differential equations, convinced that a certain property (let’s call it B) would be true if a condition (A) held, but not necessarily otherwise. To better explore the connection of A and B, I laid out two tasks in my prompt

- Give an example showcasing that if A isn’t true, then B might not be true either.

- Prove that if A is true, then B must follow. If I’m correct, a classical theorem shows that A implies another property C (but find a reference for it!), and C implies B by a standard argument.

I was quite convinced about all ingredients, except for the A implies C part. Gemini Pro, using its deep research capabilities, came back with an example to show that if A wasn’t true, B might not be either. Great! It also found a real, meaningful academic reference for C, which made me happy. But I shouldn’t have been. After carefully analyzing its work, I realized that the example it produced for point 1 actually did satisfy condition A. This meant my initial premise, that “A implies B,” was being contradicted by its own example! There was a logical hole in its argument for point 2.

I tracked down the reference for C, and it was perfectly valid. The problem, I realized, was with the AI’s crafted implication from C to B. Okay, I thought, even I make mistakes, after all, it was all my idea to prove B from C. However, when I confronted the AI with this paradox — that the only logical way out was for its C-implies-B proof to be wrong — it didn’t admit the flaw. Instead, it started hallucinating additional conditions for the A-implies-C theorem, essentially claiming that (A together with some unrelated condition D) implies C, but not A by itself. In other words, it changed history rather than admitting its fault. And despite multiple attempts, I couldn’t get the AI to correct its fundamental logical error.

This ineptitude as a Lawyer reveals why it also fails as an Architect. The core issue is a profound lack of mathematical intuition. If an AI cannot reliably tell the difference between a sound argument and a flawed one, how could it possibly succeed in the much more delicate and abstract matter of distinguishing a deep, interesting, and well-motivated problem from a trivial or pointless one? After all, what’s the point of having a perfect map if you have no idea where you want to go? The taste, the vision, and the creative dream of what is beautiful or important in mathematics remain — at least for now — a purely human domain.

The Next Frontier: From Mimicry to Reasoning

So where does that leave us? This is where the story gets even more exciting. The large language models I’ve described are only one part of the picture; a new frontier is emerging with so-called reasoning models. Unlike their cousins who master the statistical patterns of language, these tools are being built to understand and apply the actual rules of logic. They are being designed to be true Lawyers, capable of working with the cold, hard structure of a mathematical proof instead of just guessing what it should sound like.

The prospect of these reasoning models is truly transformative. Imagine having an AI colleague whose proofs you could trust as much as your own, who not only grasps your pointed-out mistakes but also naturally becomes adept at spotting flaws in your own arguments. This isn’t just about offloading tedious tasks; it’s about having a genuine, intellectually rigorous sparring partner. Such a partner would elevate the collaborative process, allowing for a far deeper and more efficient exploration of mathematical ideas. How much this will change the scenery is an exhilarating open question.

But for now, the AI we have is more like a collection of specialized apprentices than a single, all-knowing partner. Some are fast but fallible interns, others are world-class librarians, but none of them can direct the project. I don’t see this as a threat; I see my role shifting from that of a sole laborer to the director of this strange, powerful new workshop — the one who provides the vision, asks the questions, and ultimately, tells the story.

Do you have similar stories about using AI in your own field? Share your experiences! Also let us know if you are interested in more detailed stories on our adventures with maths and AI!

Member discussion: