Note: This is the first post in our new series, “The Revolutions That Made Us.” In this gallery, we’ll explore key inventions from past industrial revolutions to better understand the technological upheaval we’re living through today.

Today, we live in a world of instant downloads and AI-driven automation. It feels new, but the logic that powers our era — the relentless drive for speed, efficiency, and scale — was born over 250 years ago. Its cradle wasn’t a silicon chip, but a simple wooden machine built to spin thread. This is the story of how the Spinning Jenny and its successors didn’t just revolutionize the textile industry; they unraveled one world and wove the fabric of our own.

The Great Yarn Famine

Before the Industrial Revolution, making cloth was a human-paced art. In thousands of rural cottages, families transformed raw wool into yarn and cloth in a system known as the “cottage industry.” It was a delicate balance. It took the work of roughly four spinners (mostly women) to supply one weaver (mostly men).

Then, in 1733, John Kay’s “flying shuttle” shattered this equilibrium. By allowing a weaver to work twice as fast, his invention created a sudden and severe crisis: a “yarn famine.” Weavers sat idle, their new, faster looms hungry for thread that spinners couldn’t produce quickly enough. The market was desperate for a solution. This bottleneck reveals a core truth of the Industrial Revolution: it wasn’t a series of random inventions, but a chain reaction of problems creating demand for new solutions.

The answer came around 1764 from James Hargreaves, a poor weaver from Lancashire. His Spinning Jenny was a masterpiece of practical design. With the turn of a single wheel, one operator could now spin eight threads at once, and later, dozens. The spinning bottleneck was broken.

The Rage Against the Machine

The Jenny’s efficiency was its genius, but it was also seen as a threat. The hand-spinners whose wages had been driven up by the yarn famine now faced technological unemployment. Their response was not awe, but rage.

In 1768, a mob of spinners broke into Hargreaves’ home and smashed his machines. This was not mindless vandalism; it was a desperate act of self-preservation by skilled artisans facing oblivion. This raw, human reaction to disruption was only the beginning.

The Spinning Jenny, revolutionary as it was, still operated on a human scale that could fit in a cottage. But the technological escalation that followed was swift and decisive. Richard Arkwright’s water frame (1769) and Samuel Crompton’s spinning mule (1779) were giants by comparison. Too large and expensive for a family home and requiring the relentless power of a river, these machines demanded a new kind of space: the factory. This was the point of no return. The economic gravity was now pulling production out of scattered homes and into massive, centralized mills.

It was against this backdrop of accelerating change and the rise of the factory that the most famous resistance movement was born. Decades after the first machines were smashed, the anger had not faded — it had organized. This became the Luddite movement, which raged across England’s textile heartlands between 1811 and 1816. Operating under a mythical leader, “Ned Ludd,” they were not people who hated technology itself. The Luddites were skilled artisans who objected to machines being used in what they called a “fraudulent and deceitful” manner — specifically, to deskill their labor, drive down wages, and produce inferior goods.

To enforce their vision of fair labor, their methods became legendary. Luddites met secretly on the moors, organizing coordinated nighttime raids to destroy the machinery that most threatened their trade. The government’s response was brutal, passing laws that made machine-breaking a capital crime and deploying thousands of soldiers to suppress the rebellion. Many Luddites were executed or transported to penal colonies.

While their rebellion was ultimately crushed, their legacy is often misunderstood. The term ‘Luddite’ is not just a synonym for someone who opposes progress; it represents a rational fight for fairness and dignity in the face of wrenching economic change. It’s a plea that echoes with startling clarity in today’s debates about artificial intelligence, automation, and the future of creative and professional work.

With the Luddite resistance broken and the factory system triumphant, the transformation of labor was complete. The worker, once a semi-independent craftsman, became a “hand” — a wage laborer whose time and movements were governed by the factory whistle and the relentless rhythm of the machines.

The Two Kinds of Automation

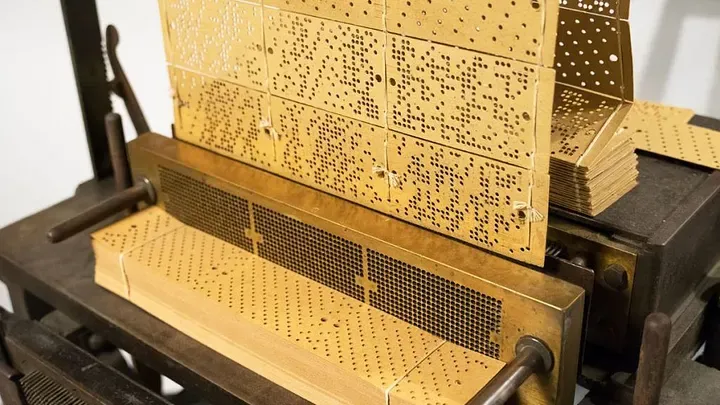

As Britain was automating physical labor, a different kind of revolution was happening in France. In 1804, Joseph-Marie Jacquard perfected a loom that automated information.

Before Jacquard, weaving complex patterns was the work of a master. Jacquard’s loom used a chain of punched cards to control the pattern. A hole in the card told the machine to lift a specific thread; no hole meant the thread stayed down. It was a binary program: hole/no-hole, 1/0. For the first time, a machine’s instructions were separated from its physical structure. A complex design could be stored as “software” on cards and replicated perfectly by any unskilled worker.

This innovation directly inspired Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace, who adapted Jacquard’s binary logic for their “Analytical Engine,” the first general-purpose computer. The textile industry thus inadvertently created two cornerstones of modernity:

- The Jenny: The automation of physical labor (leading to the assembly line).

- The Jacquard: The automation of information (leading to software).

These developments laid a clear conceptual groundwork for today’s algorithmically-driven automation.

The Empire’s New Clothes

The triumph of the British factory system cannot be told in isolation. It was underwritten by the power of the British Empire and the systematic de-industrialization of India.

Before 1750, India was a textile superpower, responsible for an estimated 25% of the world’s industrial output. Its fabrics were prized globally. But through a combination of protectionist tariffs at home and a “one-way free trade” policy in India, Britain flooded the Indian market with its own cheap, machine-made textiles while blocking Indian goods from Britain.

India’s formidable textile industry collapsed. Millions of skilled artisans were forced out of work and into poverty. India was transformed from the world’s leading textile manufacturer into a captive market and a supplier of raw cotton for British mills. The profits of the Spinning Jenny were paid for, in part, by the ruin of the weaver in Bengal.

From Mass Production to Fast Fashion

The torrent of cheap cloth from the new factories gave birth to consumerism. For the first time, ordinary people could afford more than just essential clothing. Fashion became accessible, and shopping became a leisure activity.

This logic — the relentless drive for more, faster, and cheaper — forms an unbroken thread from the first mills to the fast fashion industry of today.

- The Search for Cheap Labor: The exploitation of women and children in 19th-century British mills is the direct ancestor of modern sweatshops in low-wage countries.

- The Acceleration of Production: The seasonal fashion calendar has been compressed into the weekly or even daily “drops” of online retailers.

- The Environmental Cost: The immense waste and pollution from today’s disposable fashion culture is the logical endpoint of a system built for mass production.

Today’s fast fashion industry embodies industrial capitalism’s foundational logic, turbocharged by digital automation. Algorithms dictate design, production, and logistics, echoing the binary control of Jacquard’s loom. The Rana Plaza disaster of 2013 tragically echoed earlier industrial abuses, reminding us that mass production’s human cost persists.

Fast fashion thus represents the Industrial Revolution’s fully realized ideology. Its immense social and environmental consequences aren’t accidental; they’re embedded features of a model optimized for speed and profit, first encoded in the spinning wheels of the Jenny.

We’re still living in the world the Jenny wove — a world defined by abundance and inequality, environmental crisis, and profound ethical questions raised by technology’s relentless march forward.

The history of industrial revolutions is full of captivating stories. If there’s a chapter you’d like to explore further, let us know in the comments!

Member discussion: