How the brutal logic of the cotton gin echoes in the age of artificial intelligence.

Note: This is the second post in our series, “The Revolutions That Made Us.” In this gallery, we’ll explore key inventions from past industrial revolutions to better understand the technological upheaval we’re living through today.

Every revolutionary technology comes with a promise and a peril. It offers a solution to a problem, a leap forward in efficiency. But what happens when that new power gets plugged into an unjust system? The story of the cotton gin is a powerful answer — and a vital cautionary tale for our age of AI.

The Unprofitable Weed

In the late 1700s, slavery in America had an uncertain future. The South’s main money crop, tobacco, was ruining the soil, and fewer people were buying it. A different type of cotton, called short-staple cotton, could grow almost anywhere in the South. But it was nearly useless because its seeds were so hard to remove. A worker could spend a whole day cleaning just a single pound of cotton fiber by hand. It simply wasn’t worth the effort.

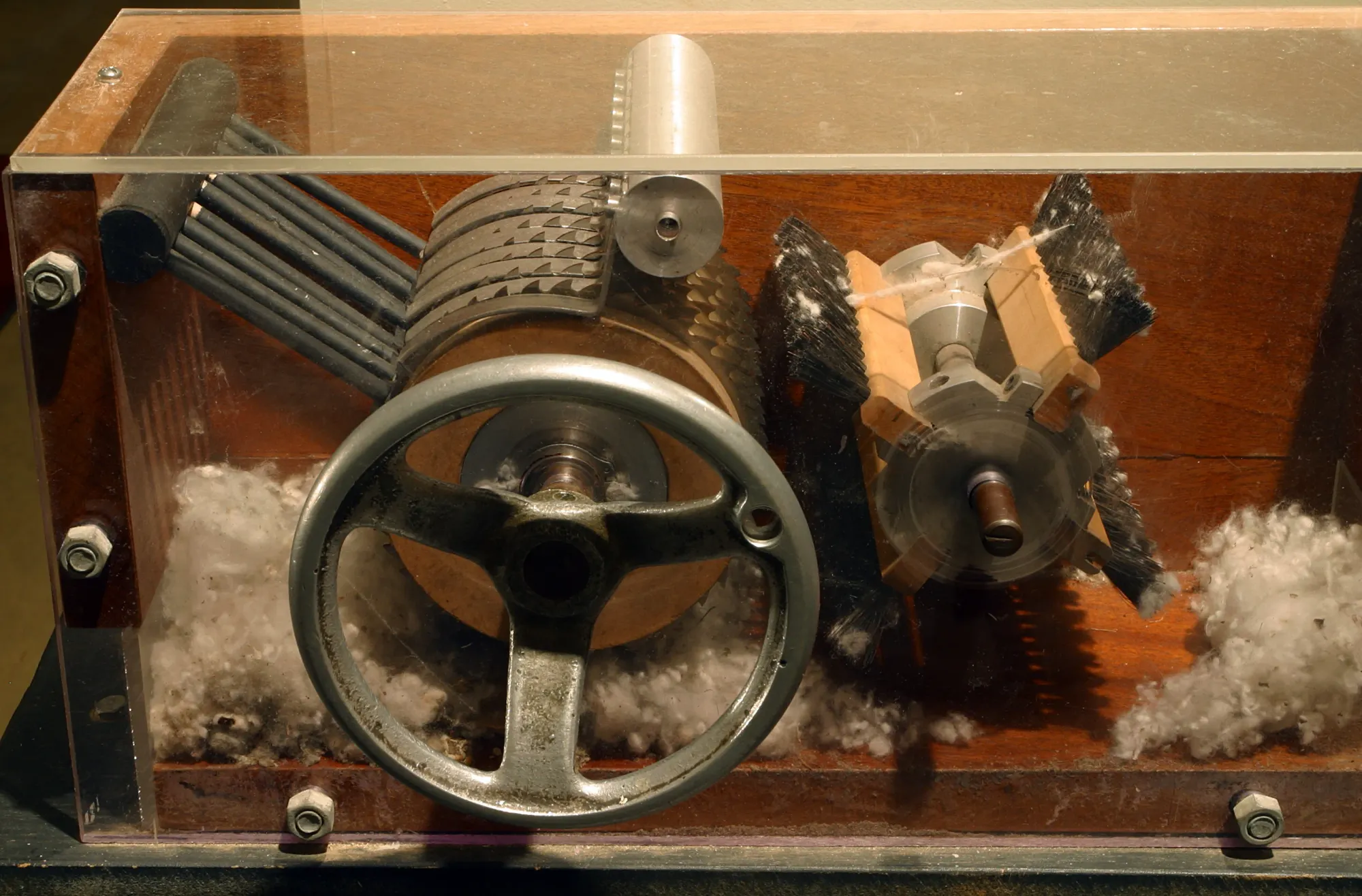

Then, in 1793, Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin. His machine was simple but effective, using a crank-powered roller with wire teeth to pull the cotton fibers away from the seeds. Suddenly, one person with a gin could clean 50 pounds of cotton in a day. This breakthrough instantly turned a worthless plant into the most profitable crop in the world.

An Engine of Injustice

The cotton gin didn’t create American slavery. But it did turn a declining institution into a brutal, industrial-scale system. This is the first crucial lesson: technology is an amplifier.

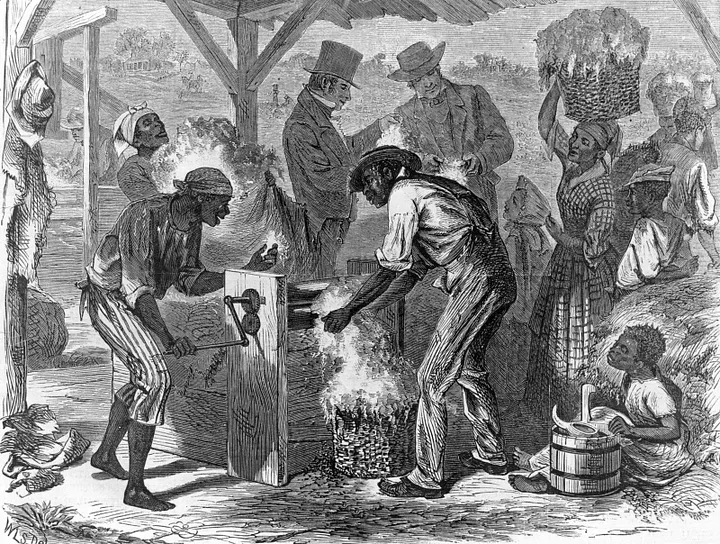

The huge demand for cotton from new factories in Great Britain and the American North created a “Cotton Kingdom” in the South. According to U.S. Census data from 1790 to 1860, the number of enslaved people grew dramatically from 700,000 to nearly four million, consistently making up nearly a third of the entire Southern population. As their numbers quadrupled, their work became more focused. By the 1850s, over half of all enslaved people in the U.S. were forced to work in the cotton fields (Gates Jr., 2011). A machine that saved labor in the barn created a massive demand for brutal human labor in the field.

We see a modern echo of this in artificial intelligence. AI doesn’t invent human bias, but it can copy and expand it on a massive scale. A clear example is the automated resume-screening tools used by many large companies. In one well-known case, Amazon in 2018 scrapped an experimental AI recruiting tool because it learned to prefer male candidates (Reuters, 2018). Because the AI was trained on a decade’s worth of the company’s hiring data — which mostly came from men — it taught itself that male-dominated resumes were better. The system even penalized CVs that included the word “women’s,” such as “women’s chess club captain.” This case shows how AI can amplify old patterns of discrimination, making them appear objective and data-driven.

The New, Brutal Workplace

The second lesson is that new jobs created by technology are not always good jobs. The cotton boom created a huge new need for cotton pickers in the Deep South. This work was exhausting, lasting from sunrise to sunset under the watch of an overseer. The efficiency of the gin was paid for by the immense suffering of the people who planted and picked the cotton. The system was optimized for profit, treating human beings like parts in a machine.

Today, we see an echo of this structure — though certainly not the same brutal conditions — in the hidden human work that powers our digital world. The AI that seems to work like magic often relies on a global workforce of low-paid people doing “microwork” (Gray & Suri, 2019). These are content moderators who must view traumatic material to keep social media clean, or workers who remotely monitor and correct self-driving cars in real-time. This labor is often stressful, unstable, and invisible to the users who benefit from it, a modern shadow of a system where a technology’s success depends on devalued human effort.

The Unforeseen Reckoning

Finally, the story of the cotton gin shows that it’s nearly impossible to predict the full impact of a revolutionary invention. While the causes of the U.S. Civil War were complex, the gin was a powerful contributing factor. By making the Southern economy almost completely dependent on cotton and slavery, it deepened the economic and political divide between the North and South. It helped create a situation where compromise seemed impossible, setting the stage for a terrible conflict.

As we live through the AI revolution, we also struggle to see the long-term effects. How will automation change our jobs and our communities? What will AI-driven surveillance and misinformation do to our society? Like the cotton gin, AI is a tool of incredible power. Its final legacy won’t be determined by its code, but by the values of the society that uses it. The hardest questions it raises aren’t about technology; they are about us.

The history of industrial revolutions is full of captivating stories. If there’s a chapter you’d like to explore further, let us know in the comments!

References

- Dastin, J. (2018, October 10). Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women. Reuters.

- Gates Jr., H. L. (2011). Life Upon These Shores: Looking at African American History, 1513–2008. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Gray, M. L., & Suri, S. (2019). Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- U.S. Census Bureau. (1790–1860). Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970.

Member discussion: